Understanding CorA’s document model — i.e., the logical representation of documents within the software — can be helpful for understanding certain aspects of the tool better, and is crucially important when trying to import your own texts into CorA. The CorA-XML file format closely reflects this model.

The main design goal for this document model was to be suitable for historical documents and other non-standard data. It tries to address the problem of tokenization by distinguishing between the appearance in the original document and the desired units of annotation. Furthermore, it keeps information about the original document layout.

Tokenization

“Token” in a general sense is the name of a unit, usually roughly corresponding to a “word”, that is processed by an NLP tool. When working with non-standard data in particular, it is not always easy to define what a “token” should be. Furthermore, the units that should be annotated might not be what is actually found in the text (e.g., when separating by whitespace), for a variety of reasons.

In CorA, virtual tokens exist purely as a container for two different types of tokenization:

-

Diplomatic tokens (sometimes called “dipl”s), which correspond to tokens as they appear in the source document. Layout information, which also relates to the document’s appearance, refers to this type of tokens. They are not relevant for the annotation and therefore currently not shown in the web interface.

-

Modernized tokens (sometimes called “mod”s), which are the units of annotation. They are displayed in the editor (each row in the editor corresponds to one modernized token) and only they can actually carry annotations.

The “virtual token” unit now acts as the smallest overarching span for any set of diplomatic and modernized tokens. This way, it connects the two tokenization layers and allows inference about the relationship between diplomatic and modernized tokens.

Note

It’s important to note that the difference between “diplomatic” and “modernized” tokens is purely one of tokenization. To put it another way, diplomatic and modernized tokens simply provide two different partitions of the underlying virtual tokens. The following examples might make this clearer.

In particular, “modernized” in this sense does not mean that the form of the token (e.g. spelling) has been modified in any way. A modernization or standardization of spelling would usually be considered to be a form of annotation layer in this model, not a property of the token itself.

Some examples

In the simplest case, virtual/diplomatic/modernized tokens are all identical. It’s not unusual if this is the case for the vast majority of tokens in your document:

| virtual token | das |

|---|---|

| diplomatic | das |

| modernized | das |

For a more interesting example, let’s take the example wordform “soltu”, a common word in historical German texts. It can be analyzed as a contraction of a verb and a pronoun, namely the modern German “sollst du” (lit. “should you”). Therefore, we decide to annotate these wordforms as two separate tokens, “solt” and “u”.1 However, we want to keep the information that, in the source manuscript, “soltu” is a single word. We could represent this in our document model in the following way:

| virtual token | soltu | |

|---|---|---|

| diplomatic | soltu | |

| modernized | solt | u |

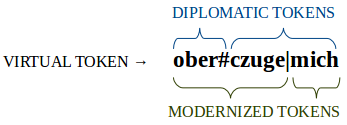

More complex cases are possible. Let’s take the (again, German) example “ober czugemich”, which would correspond to modern German “überzeuge mich” (lit. “convince me”). For some reason, the verb (“ober czuge”) is separated in the manuscript, but the pronoun (“mich”) is attached to the verb. This could be due to mistakes by the manuscript writer, or simply lack of space, but in any case we’d like to preserve that information, but still base our annotation on a more semantically appropriate tokenization of this sequence. In our document model, this would look like:

| virtual token | ober czugemich | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| diplomatic | ober | czugemich | |

| modernized | oberczuge | mich | |

Here, the relationship between the modernized “oberczuge” and the diplomatic tokens (i.e., that it consists of the first diplomatic token and parts of the second) is not expressed directly, but only indirectly via their common “virtual token” span that contains them. As mentioned before, you can view diplomatic and modernized tokens as (potentially) different subdivisions of the virtual token unit:

Token representations

Apart from the different tokenization layers described above, there are different representations of any given token as well.

-

trans: Originally for “transcription”, this is the underlying base representation of a token. It is one of the forms that can be displayed in the editor, and it is important as the basis for token editing (see below).

-

utf: Purely for viewing purposes, and one of the forms that can be displayed in the editor. This field can be used for a proper Unicode representation of a token in case the ‘trans’ form encodes special characters in some way.

-

ascii: Only for modernized tokens, this field is the opposite of ‘utf’ in that it is intended to be a simple, ASCII representation of the token. It is used as input for external annotation tools.

For example, if the transcription encodes the “long s” character ‘ſ’ as ‘$’ (e.g., for easier typing by the transcribers), a modernized token could have the following representations:

| trans | utf | ascii |

|---|---|---|

| $prach | ſprach | sprach |

When editing tokens, it is always the ‘trans’ form of the virtual token that is edited, and the other representations must be derivable from that. Examples for that include special character encodings (like the “long s” in the example above) or split marks for diplomatic/modernized tokens. For example, to represent the complex “oberczuge mich” example from above, the ‘trans’ form could include special characters to mark the token boundaries:

| trans | utf | ascii | |

|---|---|---|---|

| virtual token | ober#czuge|mich | ||

| diplomatic tokens | ober# | ober | |

| czuge|mich | czugemich | ||

| modernized tokens | ober#czuge| | oberczuge | oberczuge |

| mich | mich | mich |

Note again that the ‘trans’ forms of the virtual/diplomatic/modernized tokens only differ in tokenization, and still include the special characters (‘#’ to mark diplomatic token boundaries, ‘|’ to mark modernized token boundaries, but you are free to use different conventions), while the other representations can be anything you want, as long as they’re derivable from ‘trans’.

Here is an overview of which representations are supported by the tokenization layers:

| trans | utf | ascii | |

|---|---|---|---|

| virtual token | ✓ | — | — |

| diplomatic | ✓ | ✓ | — |

| modernized | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

Layout

Layout information is intended as a way to preserve information about the original structure of a document. This data is mainly just stored internally and shown in the “Line” column of the editor table, but cannot be modified in any way within the web interface.

Diplomatic tokens form the basis for layout information, since they represent the tokenization as found in the source document. There are three levels of layout elements:

-

Pages are at the highest level of layout elements; they can be named with up to 16 characters, so you aren’t restricted to numbers, and can optionally have a (one-character) “side” identifier (e.g., recto and verso is commonly used with historical documents).

-

Columns can subdivide pages and have a one-character name.

-

Lines can subdivide columns and have a name of up to five characters; they are the lowest level of layout elements and point to individual diplomatic tokens.

Each document layout is made up of one or more pages; each page contains one or more columns; each column contains one or more lines; and each line contains one or more diplomatic tokens. The dependency chain thus looks like this:

page → column → line → diplomatic token

If you don’t want or need all of these elements, that is fine, but you still need to include at least one of each type. For example, if you don’t need the ‘column’ element (since all of your pages have only a single column), you still need to have a “dummy” column element for each page in your document; you cannot have pages refer to lines directly.

Likewise, if you don’t want to use layout information at all, it’s fine to create exactly one “dummy” element of each type and link all diplomatic tokens to the same ‘line’, but you cannot omit these elements altogether.

Further components

The following section contains features of the document model that are currently supported, but not integrated into the web interface at this time. Unless stated otherwise, they are supported during import/export (and kept in the database), but have no functional significance. They exist mainly for historical reasons, and might be integrated in the user interface at some point, but until then, you should probably try to avoid using them.

Shift tags

Shift tags act as a mark-up for a span of tokens. They can be used to mark a certain range of tokens to be “foreign material” (e.g., Latin passages in an otherwise English text) or to have “rubricized letters”.

Token-level comments

Besides the ‘comments’ annotation layers, there is support for comments on the token-level (i.e., the virtual token of this document model). They can be given a one-letter “type” abbreviation that has no functional significance.

-

Of course, this is not the only way such cases can be handled. We do not claim that tokenizing the example in this fashion is the only, or even the “best” way to do things — the examples mainly serve to illustrate how things would be represented in CorA if we want to analyze the data in the described way. ↩